By Keith Houston (Guest Contributor)

In January 2015, scientists at the European Radiation Synchrotron Facility in Grenoble, France, announced that they had deciphered handwritten text from a series of papyrus scrolls excavated at the Roman town of Herculaneum by passing X-rays through the scrolls’ carbonized remains. Then, in March this year, another secret was revealed. Those same scrolls were discovered to have been written with distinctive metallic ink, once through to have been invented many hundreds of years later, and which boasted – or rather, whispered of – roots in ancient spycraft.

The Disappearance of Carbon Ink

Since time immemorial Roman scribes had employed a system of hollow reed pens, homemade ink, and papyrus scrolls purchased according to length. The ink in which they dipped their pens was a mixture of water, gum arabic, and soot, just as it had been for the Egyptians and Greeks before them. Gum came from the acacia trees found in Asia Minor to the East; soot, on the other hand, could be scraped off burnt cooking utensils, ground down from cremated elephant bones, or prepared in a purpose-built furnace, depending on the motivation and the means of its maker. It was a simple recipe, and a flawed one: the distinguishing feature of carbon ink was that it could be washed off papyrus scrolls with nothing more than a moistened finger. (Martial, a Roman poet of the first century CE, wrote of sending out his books still wet so that discerning patrons could erase poems not to their liking.)

Sometime during the first century, however, things began to change. As the ERSF researchers discovered, scribes at Herculaneum were using a quite different kind of ink no later than 79 CE, when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius choked the life out of the town – an ink with metallic elements in its make-up that is opaque to X-rays. The days of carbon-based ink were numbered.

A New Medium: Metal Ink

Until now, the received wisdom was that metal-based ink had become popular only during the third or fourth century CE, popularized by Christian scribes who copied and re-copied the Gospels and other important religious works. To make metallic ink, nutlike tree growths called galls were dried, crushed and infused in rainwater, wine, or beer, before being mixed with sulfate of iron or copper. The acidic gall liquor reacted with the metal sulfate as soon as the two were brought together to form an insoluble pigment that fixed itself on the page, and scribes learned to breathe into their ink jars to replace the air with unreactive carbon dioxide before stoppering them. For ancient writers, metallic ink was a quantum leap forward, as permanent on papyrus as it was on the new-fangled parchment becoming popular with scribes as far afield as Gaul and Britannia.

But the irony of metallic ink is that it may well have grown out of a need for subterfuge rather than brazen permanence. In the third century BCE, a Greek engineer named Philo wrote of what he called “sympathetic ink” made from tree galls and copper sulfate, but these familiar ingredients were to be brought together after their message had been written, not before. In Philo’s scheme, a would-be spy or illicit lover wrote on papyrus using a colorless infusion of crushed tree galls; on receipt, their correspondent washed that same papyrus with a solution of copper sulfa te to reveal its hidden message.

te to reveal its hidden message.

Work to decipher the Herculaneum scrolls is still ongoing, and we don’t yet know whether their singular metallic ink is a descendant of Philo’s recipe or something else entirely. But whatever we learn, our understanding of ancient writing practices has already been turned on its head. Metallic ink was used centuries earlier than previously thought, long before Christian monks and scribes turned their hands to it, in a Rome where citizens prayed to household shrines and where the wrath of Vulcan, god of the volcano, was still a thing to be feared.

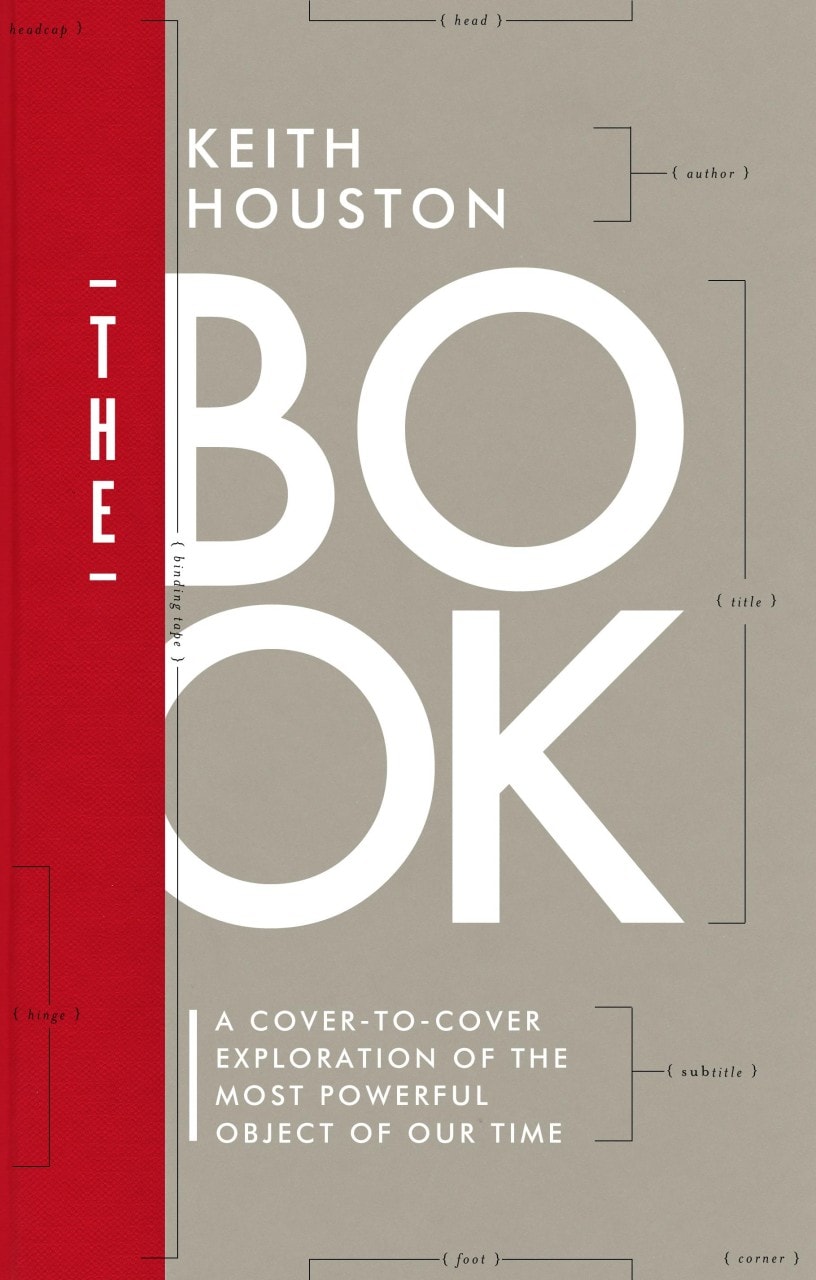

Keith Houston is the founder of shadycharacters.co.uk. His latest book, The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time, is available now from W.W. Norton & Co.