Street scene in colonial Haiti

by Philippe Girard (Guest Contributor)

Early in 1758, François Makandal stood before the church of Cap-Français, the main French town in what is today Haiti. Bearing a sign that read “Seducer, Blasphemer, Poisoner,” he was ordered to publicly confess his crimes. They included a poisoning conspiracy that had allegedly cost the lives of thousands of planters and slaves. This was a serious charge in a colony that was the most prosperous in the New World, and where hundreds of plantations produced the bulk of Europe’s sugar and coffee. Makandal’s sentence: to be burnt alive.

Executions were meant as teaching moments for the general public, so many people, both free and enslaved, gathered on the plaza in front of the church. Makandal, whose name roughly translates as “sorcerer,” claimed magical powers such as the ability to transform himself into a mosquito. As he was tied to a stake, everyone present wondered who would prevail on that day—French justice or the occult powers of Vodou.

View of Cap-Français. Makandal was executed in front of the Church.

As the flames engulfed him, Makandal fought and struggled… until he freed himself. All the slaves gasped “Makandal sauvé”! “Makandal is free!” Fearing a riot, authorities evacuated the plaza. They then tied Makandal and threw him back onto the pyre, but the public did not witness his death and a rumor soon spread among the slaves of the colony that Makandal had become a mosquito and flown away from the execution site unscathed. One day, they thought, Makandal would return to exact his revenge and free the slaves of Haiti.

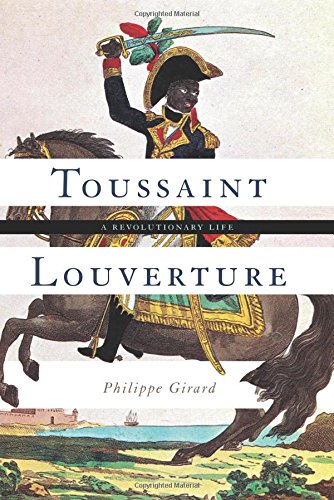

Portrait of Haitian revolution leader Toussaint Louverture by Nicolas Maurin (1832).

It is easy to dismiss such belief as artefacts from a pre-scientific age governed by superstition. But two decades later, in 1791, the slaves of Haiti did revolt against their masters. The uprising involved 500,000 slaves, one thousand times more than the largest slave revolt in US history. Amazingly, they prevailed.

Many factors contributed to the success of the Haitian slave revolt, the only successful slave revolt in the history of the world. The rebels’ courage and dedication evidently played a role. So did the extraordinary skills of their leader Toussaint Louverture, the “black Napoleon.” It was under his leadership that the slaves of Haiti repelled invasions by Spain and Britain, then a massive expedition led by Napoléon’s own brother-in-law, and eventually secured the independence of Haiti in 1804.

But equally important were successive outbreaks of yellow fever that decimated the armies sent to quell the Haitian slave revolt. One by one, European expeditionary forces were dispatched to Haiti, only to melt away as yellow fever took its toll. This was a dramatic example of the phenomenon described by William McNeill in Plagues and Peoples: history is shaped by great individuals like Toussaint Louverture, but also by natural forces like disease.

Yellow fever, we now kno w, is a virus transmitted by a mosquito, the Aedes aegypti. Maybe Makandal survived his execution after all.

w, is a virus transmitted by a mosquito, the Aedes aegypti. Maybe Makandal survived his execution after all.

Philippe Girard is a Professor of Caribbean History at McNeese State University and the author of Toussaint Louverture: A Revolutionary Life (Basic Books, November 2016) © Philippe Girard 2016.