By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

This post is adapted from an article on my personal blog,

https://sharedconversations.wordpress.com/2016/07/04/pausanias-and-agathon-a-same-sex-relationship/

In another aspect of my life, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about how the ancient Greek past is used to in current debates about sexuality and the body. During recent discussions in my church, the Church of England, around equal marriage, one of the pressure groups issued a statement giving its answers to the sorts of questions which could come up in debate. One involves using two ancient Greeks – Pausanias and Agathon – as evidence that same-sex male relationships were familiar at the time when the New Testament was written.

Without getting into any of the details of the very heated church debates here, I just want to use this example to illustrate how carefully we need to read historical sources, from any period. As an ancient historian, I’m struck by the way some people tend to use the ancient Greeks without any sense of historical context or genre. It’s as if all sources are valid in precisely the same way. To make it worse, people can just ignore a few centuries – Pausanias and Agathon lived in the fifth century BCE, while the New Testament was written in the first century CE. While the pace of change in the past wasn’t what it is now, that’s still a long gap!

Why are we using the past?

The reason why Christians today want to bring Pausanias and Agathon into their arguments – whether for or against equal marriage – is simple. As the statement says, “Some have suggested that faithful same sex relationships were not known in (pre) biblical times and therefore the bible is silent on this matter. This is not true: such relationships are acknowledged by Plato and others, and it is likely that Alexander the Great was in a same sex relationship with Hephaestion, as was Pausanius with poet Agathon.”

So the argument being made here is that those who say the Bible doesn’t mention ‘faithful same sex relationships’ because they didn’t exist are wrong: such relationships did exist, so if the Bible had wanted to mention them, it could have done. Pausanias (not Pausanius) and Agathon are important because they are taken to show that it was possible for two men to be in a long-term faithful relationship.

Comparing categories

I’ve discussed elsewhere the range of different forms of behaviour that were around in the classical Greek world and which modern readers have too readily assimilated to ‘homosexuality’: an inappropriate amount of interest in personal grooming (seen, by the ancient Greeks, as indicating far too much interest in appearing attractive to women); temporary relationships in which one man (the erastês) was older and dominant with his partner (the erômenos) being younger and passive; male friendship with a strong spiritual bond but no physical expression; and men who preferred to dress and act in a way seen as ‘feminine’. Ancient categories weren’t the same as ours, so the category of ‘faithful same sex relationship’ simply can’t be applied.

Investigating the evidence

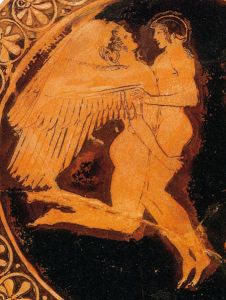

And how do we know about Pausanias and Agathon? The main source is indeed Plato, who in the Symposium imagines a conversation about love. Both Pausanias and Agathon are present, as is the playwright Aristophanes. No women are in the room, because the only woman who was there – a flute-girl – has been asked to leave. The men talk about whether love between a man and a woman is different from love between men, and conclude that the latter is better because men are, simply by being men, better. When it’s his turn to speak, Pausanias contrasts the bad sort of love, only interested in the body, with the good sort, attracted to the soul. One can feel the first sort for boys or for women, but the second sort is only felt for men. A boy should wait for the right sort of man, one who is interested in his soul rather than his body, and it is right for such a man to be given sexual access to the boy’s body.

The other main source for Agathon, a prize-winning playwright, is Aristophanes who, in his comedy Women at the Thesmophoria, has a very different Agathon: camp, and cross-dressing. Giulia Sissa identified these two Agathons – in Plato and Aristophanes – as two versions of the same man, and compares the ‘platonic glorification’ of one Agathon to the ‘comedic denigration’ of the other. So where is the real Agathon? We simply can’t say. It’s not just that in the two genres – Platonic philosophy and Athenian comedy – the same man comes out very differently, but that there’s an intertextual game going on between the two pieces of literature.

Other references to Pausanias and Agathon aren’t really additional sources, as they simply riff on Plato or copy each other. Aelian (2.21) and Xenophon (Symposium 8.32) refer to them as erastês and erômenos. The suggestion that the relationship was unusual because it went on longer than normal, beyond the point when the younger partner grows body hair, is clear. Aelian (13.4) and Plutarch (Moralia 177a) have an anecdote about the tragic poet Euripides getting drunk and kissing Agathon even though the latter was ‘about 40 years old’ (Aelian) or ‘already bearded’ (Plutarch). When challenged on this, Euripides replied ‘it’s not just spring that is excellent in attractive men – so is autumn’.

I’m not denying that Pausanias and Agathon were used in the ancient world as an example of a relationship which went on for much longer than the erastês and erômenos type normally did. But I do challenge the suggestion that we can map this on to modern relationships. To do that is to ignore genre and intertextuality in order to compare two sexual worlds that are entirely different, for both women and men: 5th century Athens and the 21st century Western world.