By Angus Trumble (Guest Contributor)

Brightly colored synthetic nail polish first crash-landed in the field of cosmetics in Paris in the 1920s, and for several decades encountered much resistance. The use of color at the fingertips was thought to conceal some sinister hint of racial impurity, or else to conceal the humble origins or grittily obscure shop-floor activities of certain female stars in the Hollywood constellation.

Pioneering advocates for African-American rights felt at first that colored women either didn’t need to use nail polish, or should avoid it on grounds of dignity. Psychiatrists attacked it as a form of self-mutilation; there were objections to color, to color and texture, to the risk to one’s health, even to the extravagant cost, which after all was not all that extravagant—hence its huge success as a global fad.

Twenty years ago the international cosmetics business was worth approximately $20 billion worldwide. Last year it was worth $250 billion. Nail polish and related products—which now include fake nails, ground coats, top coats, stenciled and other decorations, glitter, frosting, and so on—account for a significant proportion of that huge figure, while the constantly growing number of available brands, colors and textures employ ever more improbable names. “Innocent nude,” “I’m not really a waitress,” “Catherine the grape,” and “vixen” are by no means unusual, as any seasoned shopper will attest.

To some extent, through the twentieth century, nail polish went head-to-head with the declining glove trade, but not always. Rather like the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties in Britain just now, the two modes—brightly colored fingernails and a bewildering array of styles of glove—managed, via the fashion literature, very effectively to bolster each other, though it was gloves that eventually bit the dust.

I’m not sure that the new Prime Minister need worry too much about this; Queen Elizabeth II remains committed to the wearing of gloves.

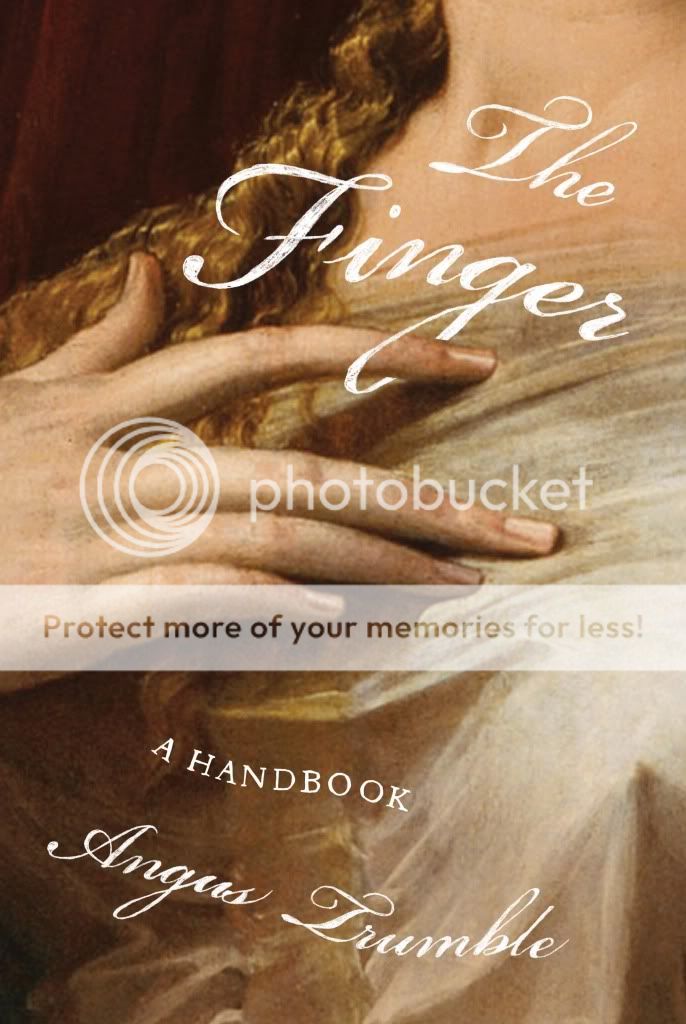

Angus Trumble was born and raised in Melbourne, Australia, and is the youngest of four brothers. Formerly the Senior Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, he is now Director of the National Portrait Gallery of Australia in Canberra, Australia. He is the author of The Finger: A Handbook

Angus Trumble was born and raised in Melbourne, Australia, and is the youngest of four brothers. Formerly the Senior Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, he is now Director of the National Portrait Gallery of Australia in Canberra, Australia. He is the author of The Finger: A Handbook and Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 23 May 2010.