By Dara Horn (Guest Contributor)

Complicating Bigotry

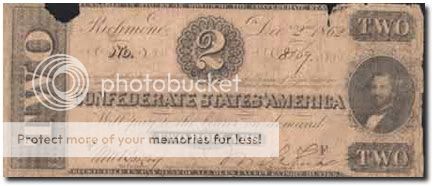

The old American South ranks high on the historical list of institutionally bigoted societies – which is why most people are surprised to learn that the Confederacy’s Secretary of State, whose face was even featured on the Confederate two-dollar bill, was a Jewish man named Judah Benjamin. But what is even more astonishing than a Jewish man’s prominence in Confederate politics was his outlandish escape from the Confederacy at the war’s end. It’s a story that makes 19th-century dime novels seem realistic.

A Multivalent Man

Judah Benjamin was one of those rare people who are described, depending on the speaker’s beliefs, as either ambitious, brilliant, craven, lucky, or blessed. Born in 1811 in the Caribbean to impoverished Jewish parents whose ancestors had been expelled from Spain in 1492, Benjamin moved with his family to the Carolinas at the age of two.

A child prodigy, he was admitted to Yale Law School at the age of 14—and if you’re wondering how on earth anyone could be admitted to Yale Law School at the age of 14, well, the people at Yale must have been wondering too, because he was expelled from Yale Law School at the age of 16. His lack of a law degree, and the persistent public anti-semitism that dogged him all his life, did not stop him from becoming a successful attorney in New Orleans, or from being elected to the United States Senate, where he represented Louisiana, or from becoming a contender for a seat on the United States Supreme Court just before Louisiana’s secession from the Union. Within the Confederacy, he had a similarly meteoric career, becoming the Confederate president’s most trusted adviser and spymaster while simultaneously serving as Secretary of State.

Yet with the Confederacy’s collapse, his indestructibility rose from mere persistence into the realm of the supernatural. As the Southern capital burned and the Confederate cabinet fled their Yankee pursuers, Benjamin recited poetry and philosophy to cheer his despairing colleagues. When Lincoln was assassinated and Northerners began to call for Confederate leaders’ executions, the cabinet refugees split up—and Benjamin’s miraculous odyssey began.

A Journey and its Ambiguous Significance

While his fellow leaders were quickly captured and imprisoned, Benjamin disguised himself as a Frenchman, wearing spectacles and speaking only French, and convincing a Jewish Confederate secret agent to pose as his “interpreter” as he traversed war-torn Georgia. When his “interpreter” abandoned him in Florida, he continued his journey alone. By then the Northern press was accusing him of involvement in Lincoln’s assassination, and there was already a price on his head.

He slept in forests and swamps by day and traveled only at night. One day as he rested in a swamp, he heard a parrot in a tree above him saying, “Hi, for Jeff! Hi, for Jeff!” At that time there was only one “Jeff” in the South: Confederate president Jefferson Davis, with whom Benjamin had spent fourteen hours a day for most of the previous four years. Reasoning that someone who had taught a parrot how to say “Hi, for Jeff!” might be sympathetic to his plight, he threw a rock at the parrot to get it out of its tree and then followed it to the home of a farmer, who indeed knew who he was, agreed to hide him for a few days, and then helped him to travel by boat along the Florida coast. Federal agents soon boarded the boat, searching for Benjamin. On his host’s suggestion, Benjamin implausibly yet successfully disguised himself, in skullcap, apron, and soot-smeared face, as the crew’s Jewish cook, and escaped capture again.

From the Florida Keys, acts of God further intervened. Benjamin boarded a small boat with two guides for the Caribbean island of Bimini, and soon found himself caught in a “waterspout” storm that the vessel barely survived. Shaken by this brush with death, he boarded another boat bound for the Bahamas. Unfortunately this boat was loaded with a cargo of sponges. The sponges gradually expanded until the boat burst at sea. Benjamin survived the wreckage in a small lifeboat that was quickly submerged within inches of sinking.

With a single oar, Benjamin and three African-American passengers on the lifeboat managed to steer their way toward the Bahamas, where Benjamin must have felt great relief to board an actual ship departing for England. By this point in the story, it is perhaps not even surprising to learn that this ship caught fire within hours of Benjamin’s boarding it – and that even though the fire raged for three days and was not even extinguished by the time the ship returned to sea from an emergency docking in St. Thomas, Benjamin nonetheless reached England unharmed. But like many ambitious or brilliant or craven or lucky or blessed people, Benjamin was not satisfied with mere survival. Instead, he embarked on an entirely new career in which he passed the British bar, became a British barrister, rose to the level of Queen’s Counsel, and wrote a textbook used in British law schools to this day.

How did this much-hated man pass through every obstacle and come out thriving on the other side? Was it ambition? Brilliance? Cravenness? Luck? Blessing?

On the Confederate two-dollar bill, Judah Benjamin is smiling. In that smile, some might wish to see a documentary-worthy sentiment like determination or courage. But I look at it and see a mask. To me, the grinning face on that two-dollar bill is the price a person once paid to thrive in a time and place where talent was not nearly enough.

Sources: Eli Evans, Judah P. Benjamin, the Jewish Confederate Robert N. Rosen, The Jewish Confederates

Dara Horn’s third novel, All Other Nights (Norton), about Jewish spies during the Civil War, is out this week in paperback. The first chapter and other information – including on Civil War ciphers and codes – are posted at www.darahorn.com

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 7 March 2010.

IMAGE: the Confederate two (2) dollar bill