by Pamela Toler

The story I’m about to tell is confusing. It’s about people you’ve never heard of, some of whom make bad decisions. In the end, people die and nothing much changes. In short, it’s a story about the West and Afghanistan.

In 1838, Dost Muhammad Khan was the Amir of Afghanistan. He had seized the throne in 1824 from Shah Mahmud, who had previously deposed his own brother, Shah Shuja. (Don’t feel sorry for Shah Shuja. He gained the throne in 1803 through a series of conspiracies that dethroned two of his brothers.) Despite the fact that he seized a throne that wasn’t his, Dost Muhammad was a popular and capable ruler who restored peace and prosperity.

In 1837, a Persian army laid siege to the Afghani city of Herat. Unable to come to terms with the British for military aid, Dost Muhammad turned to the Russians for support.

The governor-general of British India, Lord Auckland, assumed that Afghan friendship with Russia meant Afghan hostility to British India. * Based on reports from Sir William Macnaghton, the British envoy in Kabul, Auckland decided the only way to save Afghanistan from Persian and Russian aggression was to restore the elderly Shah Shuja to the throne he had lost thirty years before.

On October 1, 1838, Auckland issued the Simla Manifesto, declaring Britain’s intention of restoring the rightful king of Afghanistan to his throne. Shah Shuja would enter Afghanistan at the head of his own troops, with a little support from the British army. Once he was securely in power, the British army would withdraw.

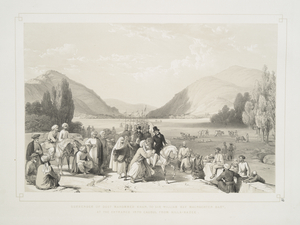

The British had been led to expect that Shah Shuja would be welcomed back on the throne with no more effort than the threat of British bayonets. Instead the Army of the Indus had to fight its way to Kabul through country that its commander, General John Keane, described as “full of robbers, plunderers and murders, brought up to it from their youth.” It took them eight months to reach Kabul and install Shah Shuja on the throne.

It quickly became clear that the only way the new Amir would stay on the throne was if the British army kept him there. The Army of the Indus became an inadequate and unwelcome army of occupation. Afghanistan was in a permanent state of unrest, with random acts of hostility and violence directed against its British occupiers.

The British leadership of the expedition was ineffectual. General Elphinstone, the commander in chief, was an elderly invalid who was no longer able to direct an army in the field and unwilling to delegate authority to his deputy. The real authority over the expedition lay with the viceroy’s envoy, Macnaghten. Under the direction of Macnaghten and Elphinstone, the British moved out of the Balla Hissar, a fortified palace outside of Kabul, and built a conventional cantonment, including a racecourse, and settled into garrison life as if they were safely in India. They even called for their families to join them.

Despite unmistakable signs of trouble, the British were completely unprepared when open revolt broke out in 1841. On November 2, an Afghan mob stormed the house of a senior British political officer who was said to have trifled with local women and murdered him and his staff. The British soon found themselves besieged in their indefensible cantonments. Efforts to clear the high ground that dominated the cantonments failed. An attempt at parley resulted in the murder of Macnaghten.

The British made the reluctant decision to retreat to India. They made a treaty with the Afghans, who guaranteed their safe conduct to India in exchange for British withdrawal from Kandahar and Jalalabad. A number of British officers and their families were held as hostages, a demand that ultimately saved their lives. On January 6, 1842, 4500 British and Indian soldiers and 12,000 wives, children and servants marched out of Kabul. On January 13, a single survivor, Doctor William Brydon, reached the British garrison at Jalalabad, sixty miles to the east. The rest were slaughtered by the Ghilzai tribesmen who controlled the mountain passes.

Shah Shuja was assassinated four months later. Dost Muhammad returned to Afghanistan the following year and ruled until his death in 1863.

* For much of the nineteenth century the British were afraid that Russia would invade India through Afghanistan. The result was the nineteenth century version of the Cold War that Rudyard Kipling dubbed “the Great Game” in Kim.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change. Her most recent book is Mankind:The Story of All of Us–a companion to an up-coming History Channel series.