By Helen Berry

Just one of the eighteenth-century equivalents of Warhol’s ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ was if a Georgian man or woman had the opportunity to make a deposition in a notorious court case. Like the stage, the witness stand presented the deponent with a captive audience, and an assemblage of journalists waiting to give their critical verdict in the gossip columns.

Just one of the eighteenth-century equivalents of Warhol’s ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ was if a Georgian man or woman had the opportunity to make a deposition in a notorious court case. Like the stage, the witness stand presented the deponent with a captive audience, and an assemblage of journalists waiting to give their critical verdict in the gossip columns.

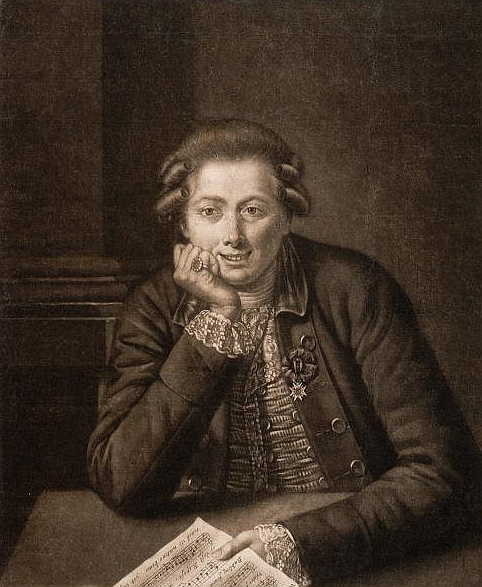

One such deponent on 6 November 1775 was Charles Baroe, a Dublin grocer and former room-mate of the Italian opera superstar Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci. Baroe had been called to give evidence in the London Consistory Court (the church court under the authority of the Bishop of London that had jurisdiction in English law over marital disputes).

The case was a libel issued by a young Irish girl, Dorothea Maunsell, for the annulment of her first marriage to Tenducci, although she was by then already married to another man, William Long Kingsman. The success of her libel rested upon the need to prove whether Tenducci was by matter of fact as well as by ‘public reputation’ a castrato.

Understandably the singer did not submit himself to the humiliation of a physical examination. Proving that Tenducci would have been unable to consummate his marriage to Dorothea was, however, required in law if the marriage was to be annulled. As Tenducci’s bedfellow, Baroe had seen the singer in a state of undress. He reported that some years earlier, back in 1765, he had asked Tenducci questions about his castration.

Obligingly, the singer ‘thereupon unbuttoned his breeches and shewed…the cicatrice or scar of the said operation, which [I]…clearly viewed, a little above the scrotum or testical bag’. Warming to his subject, Charles Baroe added additional Baroque details for the benefit of the court. In May, 1767, he recalled that he and Tenducci were again lodging together at a house in Dirty Lane, Dublin. Baroe told the court how, ‘upon…Tenducci’s changing some thing, from one pair of breeches to another’, he had observed his friend taking ‘a red velvet purse out of one pair of his breeches, to put into another’.

Baroe asked Tenducci what he had got in the bag, thinking it was a relic, to which Tenducci replied ‘No; I have got my testicles preserved in this purse, and have had them there since my castration’. Apparently, so the rumour went, the Catholic church deemed it lawful for an emasculated man to take communion, provided he had about his person the severed remnants of his manhood.

Baroe’s narrative, and selected highlights from the marriage annulment case involving Tenducci, eventually found their way into the seven-volume edition of T

rials for Adultery: or, the History of Divorces, in which readers could get their fill of ‘Adultery, Fornication, Cruelty, Impotence, etc., from the Year 1760, to the Present Time’. The public appetite for such stories appears undiminished over the centuries. But Baroe’s ‘moment of fame’, and the consequences of this court case, reveal much about how Western societies became enmeshed in moral dilemmas surrounding sex and marriage, the modification of the human body for profit, and the ultimate price of fame.

Helen Berry is Reader in Early Modern History at Newcastle University. She is the author of numerous articles on the history of eighteenth-century Britain, and is the co-editor (with Elizabeth Foyster) of The Family in Early Modern England (2007). This is her second book.