By Daisy Hay (Guest Contributor)

In the first decades of the nineteenth century Surrey Gaol in south London was one of the largest prisons in England. It held a mixture of common criminals and debtors, who lived in and around the gaol with their families. Its governor, Mr Ives, ran his establishment as a flourishing business, charging prisoners fees for ale, the services of prostitutes, the removal of chains, and even for release on acquittal by a court.

In the first decades of the nineteenth century Surrey Gaol in south London was one of the largest prisons in England. It held a mixture of common criminals and debtors, who lived in and around the gaol with their families. Its governor, Mr Ives, ran his establishment as a flourishing business, charging prisoners fees for ale, the services of prostitutes, the removal of chains, and even for release on acquittal by a court.

When the liberal journalist Leigh Hunt arrived at Surrey Gaol in 1813 to start a two year sentence for libelling the Prince Regent, he posed the prison authorities with a problem. Since he was writing about his incarceration every week in his newspaper, The Examiner, they couldn’t keep him in the spartan conditions endured by other prisoners. So they allocated him two rooms in the old infirmary, and allowed him to summon the decorators. Hunt installed crowded bookshelves and a piano, screened the barred windows with venetian blinds and covered the walls with rose-patterned wall-paper. Six weeks after the beginning of his sentence, he was ready to receive visitors.

His friends made their way through the dirty London streets and the prison’s dark corridors to find him settled in a riot of colour and comfort. He sat in splendidly appointed rooms, a fairy-tale king holding court in a bower of his own creation. His cell became an unlikely literary salon, and a refuge – for both the prisoner and his visitors – from the cares of the world.

Daisy Hay lives in London. Young Romantics: The Tangled Lives of English Poetry’s Greatest Generation

Daisy Hay lives in London. Young Romantics: The Tangled Lives of English Poetry’s Greatest Generation

is her first book.

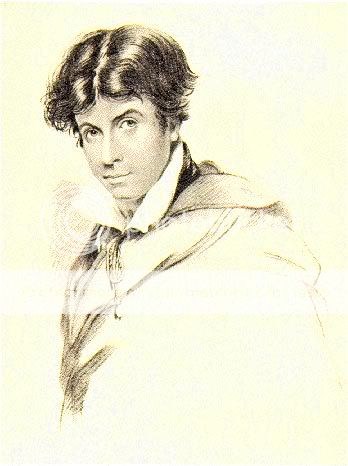

IMAGE: Leigh Hunt, Engraved by H. Meyer from a drawing by J. Hayter