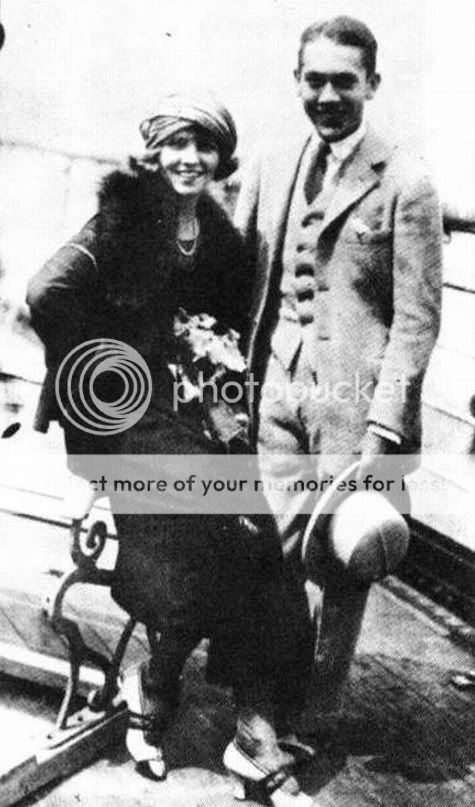

Olive Thomas and Jack Pickford

By Deborah Blum (Guest Contributor)

In the year of her death, starlet Olive Thomas, was a favorite of Hollywood gossip magazines. Married to Jack Pickford – younger brother of screen star Mary Pickford, she and her husband had a reputation for intense partying and intense quarreling, usually over his numerous side affairs – he’d developed syphilis as a result of one of them.

In early September 1920, the couple flew to Paris, reportedly on a reconciliation holiday. They checked into the Hotel Ritz and whirled off to enjoy themselves in a Prohibition-free city. After one particularly drunken spree, Pickford and Thomas staggered into their hotel room at nearly 3 in the morning.

As Pickford told the police, he was dozing when Olive began screaming “Oh my God, my God.” He stumbled into the dimly lit bathroom, where she was leaning against the counter. Mistaking it for her sleeping medicine, she had picked up a bottle of the bichloride of mercury potion that he rubbed on sores caused by syphilis, and swallowed a large dose. He carried her to the bed and called for an ambulance. “I’m poisoned,” she whispered.

As the story broke, newspapers spread the rumors: his infidelities had driven her to suicide; he’d tricked her into taking poison. By the time she died three days later, he was a murder suspect.

But the police investigation concluded that it was, as Pickford had said, just a terrible accident. They happened frequently. In New York City, the medical examiner calculated that mercury bichloride caused about 20 deaths a year. Still Thomas had definitely given the poison a fleeting star status.

Deborah Blum is a professor of science journalism at the University of Wisconsin and author of The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York.