By Miranda Garno Nesler (Guest Contributor)

By Miranda Garno Nesler (Guest Contributor)

Performance on and off Stage

Charles I of England is infamous for his love of performance. Indeed, masques—lengthy performances in which professional actors portrayed chaos while silent noble actors danced to represent the return of order—were a favorite pass-time. He was, indeed, one of the few English kings who consistently tread stage boards as a performer. Not only was he present in utero during his mother’s infamous performance in The Masque of Blackness; but Charles also began entertaining on his own as a toddler, back when he was titled Duke of York and Albany and was second in line to the throne. He often onstage as symbols of English patriarchal power like Zephyr in masques like Tethys’ Festival. The tiny Charles amused courtiers and supported his father’s kingship by dancing at the Banqueting House of Whitehall Palace. Because his mother, Queen Anna of Denmark, had an affection for masque, little Charles costarred with her in numerous Banqueting House entertainments.

By the time Charles ascended to the throne, he had not lost his love of theatre. Upon marrying Henrietta Maria of France, he and his consort continued the rich tradition of masquing. Not only did they both appear onstage together; they utilized Caroline masques to foster their belief in royal power and in marital platonic love. Now closely linked to French tradition, Charles I’s court could experience masques in which noble performers not only danced, but also spoke and sang. Charles and Henrietta Maria even went so far as to refurbish the Banqueting House, making it richer with paintings commissioned by Ruben.

Performance in Death (or, a Death Masque)

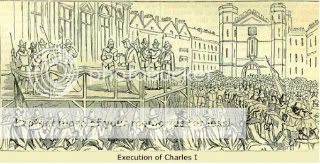

In 1649, Charles I was faced with execution. Despite being at an existential disadvantage, the intrepid king was determined to put his own performative mark on the proceedings. Even till the end, he turned to the masque tradition to bolster his own authority as God’s elect; he used the scaffold as a stage on which to highlight his successful performance on the throne.

According to the official report, at 10:00 in the morning musketeers marched King Charles I from St. James’s; by 2:00 that afternoon, he walked through the Banqueting House and onto an adjoining scaffold. Here, on the site of so many prior performances, Charles engaged the rapt crowd. “I shall be little heard of anybody here, I shall therefore speak a word unto you here,” he addressed those nearest the scaffold edge, projecting his voice. “But I think it is my duty to God first and to my country for to clear myself both as an honest man, and a good King, and a good Christian.”

After neatly outlining each of his defense points, Charles felt satisfied that he had properly narrated his own story. Charles turned to the executioner, directing him as if on stage: “I shall say but very short prayers, and when I thrust out my hands—.” After neatly arranging his hair, Charles went on to briefly close his eyes, clasp his hands upon his chest and, in a dramatic gesture, thrust his arms out before him. And, just as dictated, the ax fell and Charles I ended his final performance at the Banqueting House amid gasps and cheers.

Miranda Garno Nesler teaches English at Vanderbilt University. Currently she is working on a book project about Stuart women’s drama and the relationships among closet drama, masque, and commercial theatre.

Sources:

“King Charles, His Speech Made upon the SCAFFOLD at Whitehall Gate Immediately before his execution on Tuesday the 30 of Jan. 1948 With a relation of the maner of His going to Execution.” London: Peter Cole, 1649.

Jean E. Graham “The Performing Heir in Jonson’s Jacobean Masques.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 41, No. 2, Tudor and Stuart Drama (Spring, 2001), 381-398.

This post first appeared in W&M on 7 August 2009.